The Russian military shelling the nuclear power plant in Ukraine "trumps" that Trump nonsense. It's time for NATO to intervene on the side of Ukraine.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Ukraine Crisis

- Thread starter annabenedetti

- Start date

way 2 go

Well-known member

evidence russian military shelling the nuclear power plant ?The Russian military shelling the nuclear power plant in Ukraine "trumps" that Trump nonsense.

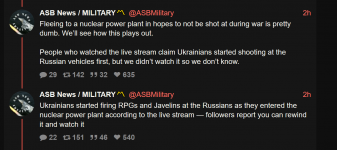

ASB News / MILITARY〽️ (@ASBMilitary)

BREAKING: Early and unverified reports of a fire at the Zaporozhye nuclear power plant

It's time for NATO to intervene on the side of Ukraine.

no

Error

ok doser

lifeguard at the cement pond

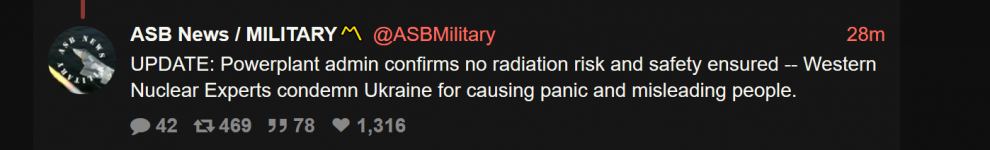

U.N. Atomic Agency Says Fire at Ukrainian Nuclear Power Plant Didn't Affect Essential Equipment

Ukrainian officials said Russian shelling caused a fire at a nuclear power plant in Ukraine, prompting concern from the international community about a nuclear disaster and renewed fears about Moscow’s tactics as it continues its advance in the country. In Kyiv, officials told the International Ato

So says that model of virtue, George Soros.It's time for NATO to intervene on the side of Ukraine.

Idolater

"Matthew 16:18-19" Dispensationalist (Catholic) χρ

How exactly do you propose to do that without starting WWIII? I mean, they've got us all over a barrel right now. They can lay waste to the whole country and murder every last soul, and we still can't do anything militarily.The Russian military shelling the nuclear power plant in Ukraine "trumps" that Trump nonsense. It's time for NATO to intervene on the side of Ukraine.

annabenedetti

like marbles on glass

Analysis from Tom Nichols here:

A few days ago, I was watching footage of Ukrainian mothers, panicked and crying, trying to evacuate their children from a beautiful city that a paranoid dictator has now turned into a war zone. I looked over at my wife, sitting a few feet away from me, and saw the tears welling in her eyes. I felt helpless. And for once, I was at a loss for words.

Night after night I find myself staring at the television, almost paralyzed with anger and grief. Russian President Vladimir Putin, after a catastrophic strategic miscalculation, is now embroiled in perhaps the greatest military blunder in modern European history. In his desperation, he is resorting to the classic Russian military playbook of indiscriminate and massive violence. His unprovoked war of aggression is rapidly escalating into war crimes.

It’s going to get worse. The images and sounds from these first few days are a mere prologue to what will come once Putin realizes that he is on track to lose this war, even if he somehow “wins” by flattening entire cities.

In my rage, I want someone somewhere to do something. I have taught military and national-security affairs for more than a quarter century, and I know what will happen when a 40-mile column of men and weapons encircles a city of outgunned defenders. I want all the might of the civilized world—a world of which Putin is no longer a part—to obliterate the invading forces and save the people of Ukraine.

Others share these impulses. In recent days, I’ve heard various proposals for Western intervention, including support for a no-fly zone over Ukraine from former NATO Supreme Allied Commander General Philip Breedlove and the Russian dissident Garry Kasparov, among others. Social media is aflame with calls to send in American troops against the invading Russians.

And yet, I still counsel caution and restraint, a position I know many Americans find impossible to understand. Every measure of our outrage is natural, as are the calls for action. But emotions should never dictate policy. As President Joe Biden emphasized in his State of the Union address, we must do all we can to aid the Ukrainian resistance and to fortify NATO, but we cannot become involved in military operations in Ukraine.

I realize that this is easy for me to say. I am not in Kyiv, trying to spirit my child to safety. I am not watching the Russians approach my town. When I finish writing this, I will reassure my wife and sit down to share dinner with her in a quiet home on a peaceful street.

But public figures and ordinary voters who are advocating for intervention also do so from the comfort of offices and homes where they can sound resolute by employing clinical euphemisms such as no-fly zone when what they mean is “war.” For now, fidelity to history requires us to remember that this isn’t the first time we’ve had little choice but to stand by and watch a dictator murder innocents.

In some cases we were unwilling to bear the costs of intervention. In others, we were deterred by the immense risks of a nuclear confrontation. During the Cold War, we did not face down the Soviets in Hungary in 1956 or Czechoslovakia in 1968. We did not send troops to drive them from Afghanistan after their 1979 invasion. (In Afghanistan, we provided material assistance to raise the cost of occupation, and we succeeded in helping the local population inflict serious wounds on the Soviet war machine, but hundreds of thousands of Afghans were dead and millions had fled as refugees by the time the Soviets threw in the towel.)

In the 1990s, we allowed war crimes and ethnic cleansing to reach horrific levels in Rwanda and the former Yugoslavia. More recently, America chose to stand aside as the Syrian regime used chemical weapons against civilians in a war that has taken well over half a million lives (a disaster that I have argued, repeatedly, justifies global military intervention). We pointedly avoided too much criticism of the Russian war in Chechnya and now do the same with regard to Chinese crimes against the Uyghurs.

I am recounting this litany of shame not as a device for consigning the Ukrainians to oblivion, but to remind us all that this is not the first humanitarian outrage we’ve seen. The day may come, and sooner than we expect, when we have to fight in Europe, with all the risks that entails. If we are to plunge into a global war between the Russians and the West, however, it needs to be based on a better calculus than pure rage. (It also will require a vote of assent from all 30 NATO nations, something that is not currently even a remote possibility.)

Also, let’s remember that America is, in fact, taking action to help Ukraine and oppose Russia. Western sanctions will not save Kyiv or other Ukrainian cities tomorrow, but they are crippling the Russian economy and undermining Putin’s ability both politically and materially to seek a larger war. We are working with the rest of the world to get military assistance to the Ukrainians, who will be fighting a resistance for as long as the Russians are in their country.

More important, we are sending more forces to our allies around Ukraine. If Putin reckoned on a quick victory and a dash to the West, that dream is over. He’ll win on the ground in the short run, but in the end he’ll be lucky to get out of Ukraine with his military intact—if he’s even still in power.

Indeed, one more reason not to let our emotions get the better of us is that the only way Putin can save himself from his own fiasco is to bait the West into an attack. Nothing would help him more, at home or abroad, than if the United States or any other NATO country were to enter direct hostilities with Russian forces. Putin would then use the conflict to rally his people and threaten conventional and nuclear attacks against NATO. He would become a hero at home, and Ukraine would be forgotten.

In thinking about all of this, I have been reliving a moment from 1991, when I was working on Capitol Hill as personal staff for foreign and defense affairs to the late Senator John Heinz of Pennsylvania. Saddam Hussein had invaded Kuwait and we were at war. The Iraqi dictator was launching Scud missiles into neighboring states, including Israel. One night, Heinz and I were walking along North Capitol Street on our way back to the office. It was a lovely evening, but we had just been told—erroneously—that Saddam had struck Tel Aviv with chemical weapons.

I was barely 30 years old. I had never been near a war. I had recently visited Israel, and I was practically shaking with rage. “Ever been to Tel Aviv, Senator? Nice city.” It was an utterly inane comment; of course the senator had been to Tel Aviv. I was just trying to make conversation, because I didn’t know what else to say while thinking about Israelis dying in the street.

Heinz paused. In a fatherly manner, he said: “Tom, I know that right now you’d like to rip Saddam Hussein apart with your bare hands. But this is when I need you to be calm and rational and helpful so that we can figure this thing out.”

It was a reproach, but a gentle one. I never forgot it, and now I always try to keep in mind that in moments of crisis, we must reflect deeply and dispassionately before daring to act.

I am as enraged today as I was on North Capitol Street more than 30 years ago. But I am trying to be calm and rational, and yes, helpful, as much as I can be. So should we all.

A few days ago, I was watching footage of Ukrainian mothers, panicked and crying, trying to evacuate their children from a beautiful city that a paranoid dictator has now turned into a war zone. I looked over at my wife, sitting a few feet away from me, and saw the tears welling in her eyes. I felt helpless. And for once, I was at a loss for words.

Night after night I find myself staring at the television, almost paralyzed with anger and grief. Russian President Vladimir Putin, after a catastrophic strategic miscalculation, is now embroiled in perhaps the greatest military blunder in modern European history. In his desperation, he is resorting to the classic Russian military playbook of indiscriminate and massive violence. His unprovoked war of aggression is rapidly escalating into war crimes.

It’s going to get worse. The images and sounds from these first few days are a mere prologue to what will come once Putin realizes that he is on track to lose this war, even if he somehow “wins” by flattening entire cities.

In my rage, I want someone somewhere to do something. I have taught military and national-security affairs for more than a quarter century, and I know what will happen when a 40-mile column of men and weapons encircles a city of outgunned defenders. I want all the might of the civilized world—a world of which Putin is no longer a part—to obliterate the invading forces and save the people of Ukraine.

Others share these impulses. In recent days, I’ve heard various proposals for Western intervention, including support for a no-fly zone over Ukraine from former NATO Supreme Allied Commander General Philip Breedlove and the Russian dissident Garry Kasparov, among others. Social media is aflame with calls to send in American troops against the invading Russians.

And yet, I still counsel caution and restraint, a position I know many Americans find impossible to understand. Every measure of our outrage is natural, as are the calls for action. But emotions should never dictate policy. As President Joe Biden emphasized in his State of the Union address, we must do all we can to aid the Ukrainian resistance and to fortify NATO, but we cannot become involved in military operations in Ukraine.

I realize that this is easy for me to say. I am not in Kyiv, trying to spirit my child to safety. I am not watching the Russians approach my town. When I finish writing this, I will reassure my wife and sit down to share dinner with her in a quiet home on a peaceful street.

But public figures and ordinary voters who are advocating for intervention also do so from the comfort of offices and homes where they can sound resolute by employing clinical euphemisms such as no-fly zone when what they mean is “war.” For now, fidelity to history requires us to remember that this isn’t the first time we’ve had little choice but to stand by and watch a dictator murder innocents.

In some cases we were unwilling to bear the costs of intervention. In others, we were deterred by the immense risks of a nuclear confrontation. During the Cold War, we did not face down the Soviets in Hungary in 1956 or Czechoslovakia in 1968. We did not send troops to drive them from Afghanistan after their 1979 invasion. (In Afghanistan, we provided material assistance to raise the cost of occupation, and we succeeded in helping the local population inflict serious wounds on the Soviet war machine, but hundreds of thousands of Afghans were dead and millions had fled as refugees by the time the Soviets threw in the towel.)

In the 1990s, we allowed war crimes and ethnic cleansing to reach horrific levels in Rwanda and the former Yugoslavia. More recently, America chose to stand aside as the Syrian regime used chemical weapons against civilians in a war that has taken well over half a million lives (a disaster that I have argued, repeatedly, justifies global military intervention). We pointedly avoided too much criticism of the Russian war in Chechnya and now do the same with regard to Chinese crimes against the Uyghurs.

I am recounting this litany of shame not as a device for consigning the Ukrainians to oblivion, but to remind us all that this is not the first humanitarian outrage we’ve seen. The day may come, and sooner than we expect, when we have to fight in Europe, with all the risks that entails. If we are to plunge into a global war between the Russians and the West, however, it needs to be based on a better calculus than pure rage. (It also will require a vote of assent from all 30 NATO nations, something that is not currently even a remote possibility.)

Also, let’s remember that America is, in fact, taking action to help Ukraine and oppose Russia. Western sanctions will not save Kyiv or other Ukrainian cities tomorrow, but they are crippling the Russian economy and undermining Putin’s ability both politically and materially to seek a larger war. We are working with the rest of the world to get military assistance to the Ukrainians, who will be fighting a resistance for as long as the Russians are in their country.

More important, we are sending more forces to our allies around Ukraine. If Putin reckoned on a quick victory and a dash to the West, that dream is over. He’ll win on the ground in the short run, but in the end he’ll be lucky to get out of Ukraine with his military intact—if he’s even still in power.

Indeed, one more reason not to let our emotions get the better of us is that the only way Putin can save himself from his own fiasco is to bait the West into an attack. Nothing would help him more, at home or abroad, than if the United States or any other NATO country were to enter direct hostilities with Russian forces. Putin would then use the conflict to rally his people and threaten conventional and nuclear attacks against NATO. He would become a hero at home, and Ukraine would be forgotten.

In thinking about all of this, I have been reliving a moment from 1991, when I was working on Capitol Hill as personal staff for foreign and defense affairs to the late Senator John Heinz of Pennsylvania. Saddam Hussein had invaded Kuwait and we were at war. The Iraqi dictator was launching Scud missiles into neighboring states, including Israel. One night, Heinz and I were walking along North Capitol Street on our way back to the office. It was a lovely evening, but we had just been told—erroneously—that Saddam had struck Tel Aviv with chemical weapons.

I was barely 30 years old. I had never been near a war. I had recently visited Israel, and I was practically shaking with rage. “Ever been to Tel Aviv, Senator? Nice city.” It was an utterly inane comment; of course the senator had been to Tel Aviv. I was just trying to make conversation, because I didn’t know what else to say while thinking about Israelis dying in the street.

Heinz paused. In a fatherly manner, he said: “Tom, I know that right now you’d like to rip Saddam Hussein apart with your bare hands. But this is when I need you to be calm and rational and helpful so that we can figure this thing out.”

It was a reproach, but a gentle one. I never forgot it, and now I always try to keep in mind that in moments of crisis, we must reflect deeply and dispassionately before daring to act.

I am as enraged today as I was on North Capitol Street more than 30 years ago. But I am trying to be calm and rational, and yes, helpful, as much as I can be. So should we all.

Idolater

"Matthew 16:18-19" Dispensationalist (Catholic) χρ

Everybody's invited to WWIII if it ever happens.It isn't a world war if South America isn't invited.

Yeah, I know.Everybody's invited to WWIII if it ever happens.

I just deleted my "not so funny" post, as you replied to it.

I wonder what the difference is between a Russian invasion of Ukraine and of Poland?

Any government leader who abuses his leadership to gain access and control over a nation's majority against their collective will is a tyrant who needs to be severely punished. This goes for domestic and foreign tyrants.The "great" crime Putin and associated committed was invading an independent country with no provocation and his actions are rightfully condemned around the world. If you endorse or even remotely make excuses for the actions of this despotic dictator then you are beyond an idiot.

Oh, don't bother with your "confession through projection" garbage either if you happen to *respond*.

Do you now see how silly the fake democrat Trump/Russian conspiracy theory was now that we understand the truth of what really happened in contradiction to lying leftist democrat claims?The Russian military shelling the nuclear power plant in Ukraine "trumps" that Trump nonsense. It's time for NATO to intervene on the side of Ukraine.

America is not served well by extremists on the left or right who do not honor God and look to Jesus for the solution to the world's problems.

Do you now see how silly the fake democrat Trump/Russian conspiracy theory was now that we understand the truth of what really happened in contradiction to lying leftist democrat claims?

Do you now see how silly the fake democrat Trump/Russian conspiracy theory was now that we understand the truth of what really happened in contradiction to lying leftist democrat claims?

Do you now see how silly the fake democrat Trump/Russian conspiracy theory was now that we understand the truth of what really happened in contradiction to lying leftist democrat claims?

Workers inside Europe’s biggest nuclear power station are being forced to operate the facility “at gunpoint” after Russian forces attacked and seized it overnight, according to the company that runs the plant. The Zaporizhzhia plant was hit by a Russian projectile Thursday night, according to the International Atomic Energy Agency, causing a fire to break out. Petro Kotin, the head of the state-owned nuclear power firm Energoatom, gave more details about the attack in a Telegram post Friday. According to CNN, Kotin said Russian troops “entered the territory of the nuclear power plant, took control of the personnel and management of the nuclear power plant.” He added: “The station management works at invaders’ gunpoint.”

Staff at Seized Ukraine Nuclear Plant ‘Working at Gunpoint’

The head of the company that runs the plant says management are being forced to keep working.

Trump did not help Putin do that, Biden did.

Biden gave Putin billions of dollars in bonus money by robbing America of its own oil production and casting the US at the feet of Putin for imported oil.

Idolater

"Matthew 16:18-19" Dispensationalist (Catholic) χρ

Nobody needed to help Putin be Putin. Putin did that all on his own.Trump did not help Putin do that, Biden did.