You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

The coronavirus scam

- Thread starter Jefferson

- Start date

way 2 go

Well-known member

Leaky Vaccines Enhance Spread of Deadlier Chicken Viruses

Over the past fifty years, Marek’s disease—an illness of fowl—has become fouler. Marek’s is caused by a highly contagious virus, related to those that cause herpes in humans. It spreads through the dust of contaminated chicken coops, and caused both paralysis and cancer. In the 1970s, new...

Published July 27, 2015

• 7 min read

Over the past fifty years, Marek’s disease—an illness of fowl—has become fouler. Marek’s is caused by a highly contagious virus, related to those that cause herpes in humans. It spreads through the dust of contaminated chicken coops, and caused both paralysis and cancer. In the 1970s, new vaccines brought the disease the under control. But Marek’s didn’t go gently into that good night. Within ten years, it started evolving into more virulent strains, which now trigger more severe cancers and afflict chickens at earlier ages.

Andrew Read from Pennsylvania State University thinks that the vaccines were responsible. The Marek’s vaccine is “imperfect” or “leaky.” That is, it protects chickens from developing disease, but doesn’t stop them from becoming infected or from spreading the virus. Inadvertently, this made it easier for the most virulent strains to survive. Such strains would normally kill their hosts so quickly that they’d die out. But in an immunised flock, they can persist because their lethal nature has been neutered. That’s not a problem for vaccinated individuals. But unvaccinated birds are now in serious trouble.

This problem, where vaccination fosters the evolution of more virulent disease, does not apply to most human vaccines. Those against mumps, measles, rubella, and smallpox are “perfect:” They protect against disease and stop people from transmitting the respective viruses. “You don’t get onward evolution,” says Read. “These vaccines are very successful, highly effective, and very safe. They have been a tremendous success story and will continue to be so.”

He is more concerned about the next generation of vaccines that are being developed against diseases like HIV and malaria. People don’t naturally develop life-long immunity to these conditions after being infected, as they would against, say, mumps or measles. This makes vaccine development a tricky business, and it means that the resulting vaccines will probably leak to some extent. “This isn’t an argument against developing those vaccines, but it is an argument for ensuring that we carefully check for transmission,” says Read.

“The candidate Ebola vaccines are also foremost in my mind,” he adds. “Some of the monkey trials suggest that they may be perfect, but we need to be very confident that they don’t leak. If they do, and some vaccinated individuals are capable of passing on Ebola, that might lead to the evolution of very dangerous pathogens.”

way 2 go

Well-known member

way 2 go

Well-known member

way 2 go

Well-known member

stuck on stupid

way 2 go

Well-known member

ok doser

lifeguard at the cement pond

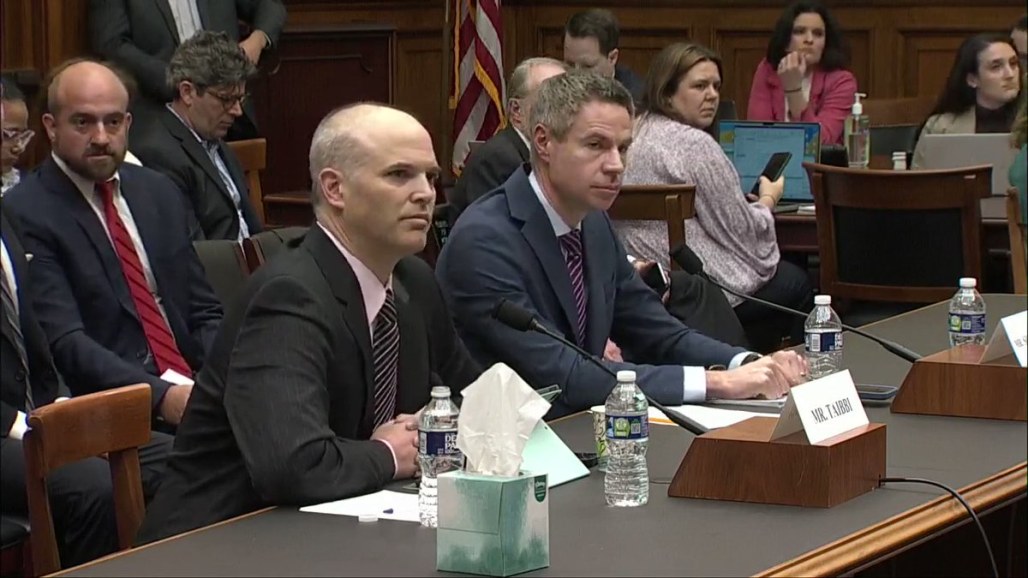

Fun fact! If you challenge the official narrative, you're a racist!Ingraham's take on the testimony that indicts Fauci

way 2 go

Well-known member

☕️ TIMES AND CURSES ☙ Friday, March 10, 2023 ☙ C&C NEWS 🦠

A special roundup of hot takes and gotchas to tide you over till Saturday.

ok doser

lifeguard at the cement pond

My life was back to normal in January of 2020

way 2 go

Well-known member

not here butMy life was back to normal in January of 2020

I was the first to take down the plastic barriers at work sometime last year

but it took until last month for them to all disappear .