You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

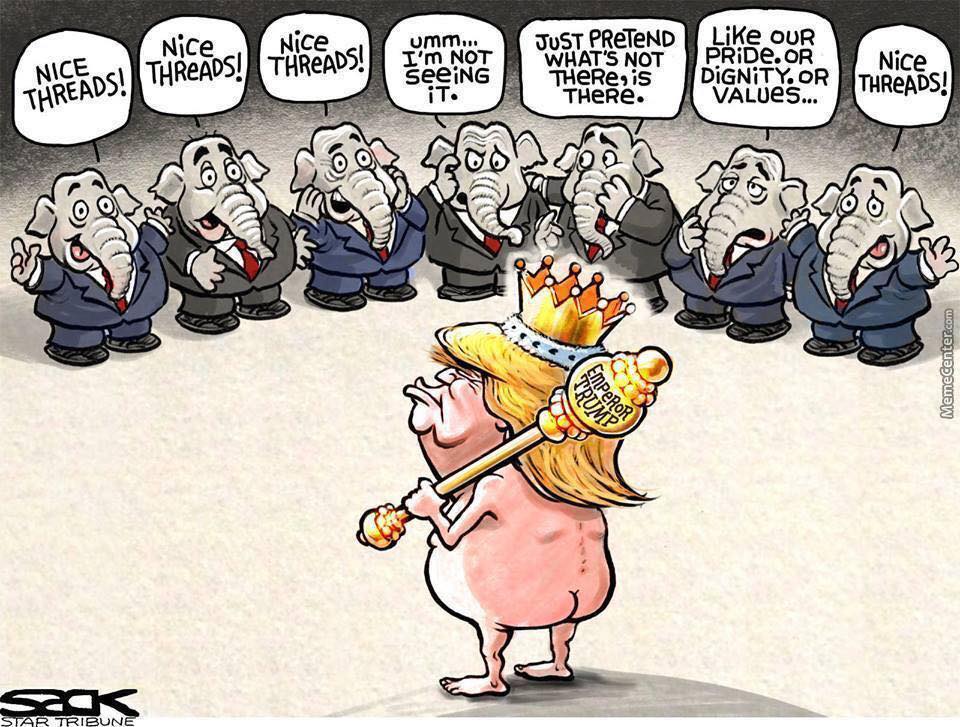

The long nightmare has just begun: Inauguration of a fraud.

- Thread starter annabenedetti

- Start date

I can't go to the WAPO, they want too much information and they want me to remove Ad Block

exminister

Well-known member

The dark side of Trump’s much-hyped China trade deal: It could literally make you sick

Link

The first known shipment of cooked chicken from China reached the United States last week, following a much-touted trade deal between the Trump administration and the Chinese government.

But consumer groups and former food-safety officials are warning that the chicken could pose a public health risk, arguing that China has made only minor progress in overhauling a food safety regime that produced melamine-laced infant formula and deadly dog biscuits.

Chicken from China will not be labeled, and a representative from Qingdao Nine-Alliance Group, the first exporter, did not specify the name brand it’s being sold under. The privately owned chicken company, one of the largest in China, already supplies markets in Asia, the Middle East and Europe.

Exports of poultry, largely chicken and duck, are expected to swell under the terms of a May trade deal that would send more U.S. beef to China and expand Chinese poultry sales into the United States. The U.S. Department of Agriculture recently proposed a rule allowing China not only to cook, but also raise and slaughter the birds that it ships here as chicken nuggets and flash-steamed duck breasts.

President Trump has tweeted his enthusiasm about the deal, describing it as “REAL news!” Agriculture Secretary Sonny Perdue has championed it as a win for American industry, even as he promises that inspectors will stop contaminated meat from reaching U.S. consumers.

“Well the good thing about it is our food safety inspection agency in the USDA does a marvelous job,” Perdue said on CNBC last month. “They’ve looked for years over the equivalence of the inspection.”

Critics are accusing the Trump administration of risking public health to open up foreign markets.

“Taking that processed chicken was a quid pro quo to get China to accept U.S. beef,” said Rep. Rosa L. DeLauro (D-Conn.), an outspoken critic of the agreement. “Trade always trumps public health in the U.S. … It’s outrageous. It says we don’t care about the health and safety of consumers.”

Under current regulations, China may only export cooked chicken products to the United States. And while those products can be processed and packaged in China, the birds must be raised and slaughtered in Canada, Chile or the United States.

Those rules are based on long-standing concerns about China’s poultry farming and slaughter operations, particularly in regards to avian influenza.

Because cooking kills bacteria and viruses, including the one that causes bird flu, processed poultry is considered “tremendously safer” than raw chicken, said Richard Raymond, who served as undersecretary of agriculture for food safety from 2005 to 2008.

The most significant risk in a cooked poultry product is an environmental contaminant, such as listeria, or a residue or intentional adulterant, such as the melamine that surfaced in Chinese infant formula.

Birds sourced from a USDA-approved country, like Canada or Chile, are guaranteed to undergo the same safety checks during slaughter that they would in the United States.

But Chinese trade negotiators have consistently pushed for better access to the nearly $30 billion U.S. broiler chicken market, particularly for Chinese-raised and Chinese-slaughtered birds. As part of joint economic talks earlier this year, the United States agreed to begin receiving Chinese-raised, processed chicken “as soon as possible.”

The Department of Agriculture has since proposed a rule allowing Chinese-raised chicken into the United States, which could be finalized by the end of the year. A representative of Qingdao Nine-Alliance said the company sent its first shipment in order to “study the procedure and documentation for export to [the] U.S.” ahead of that anticipated liberalization.

In exchange, and as part of the same economic talks, China agreed to lift its 14-year ban on most beef from the U.S., a historic pain point in bilateral negotiations. The ban, which originated after an outbreak of mad cow disease in 2003, has cut American beef producers out of an exploding $2.5 billion import market.

At times, Chinese negotiators have intimated that they would also limit U.S. access to other commodity markets if Chinese poultry was not approved, former USDA officials said. Agriculture is one of the few major areas where the United States maintains a large trade surplus with China.

Beef producers have been effusive in their praise of the agreement. So have Trump administration officials, who have heralded it as proof that the president’s trade tactics work. In a statement, Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross called the deal “even more concrete progress” in Trump’s quest to “improve the U.S.-China relationship.”

But many food-safety experts are less sure that the deal represents a step forward, particularly if it results in a surge of Chinese chicken exports to the United States. China has experienced repeated episodes of both avian influenza and food contamination — a situation that the country’s own food safety chief admitted in December, when he told China’s National People’s Congress that there were still “deep-seated problems” in the Chinese food system.

“When you look at China, it has a very spotty history with food safety,” said Brian Ronholm, who served as deputy undersecretary of food safety at USDA until January of this year. “It’s very easy to fear the worst.”

Among China’s biggest issues is the presence of several highly lethal and contagious strains of avian influenza, which has killed more than 270 people and closed a number of poultry markets since October. The risk of bird flu is what prevents China from exporting raw chicken.

The country has struggled to standardize food safety practices and oversight in its processing plants, which have contributed to a long list of contamination scandals. Instead, China has historically left food-safety oversight to individual manufacturers — some of whom are not well educated or attentive to food safety practices, said Sebastien Breteau, the chief executive of AsiaInspection, which audits the supply chains of food multinationals.

Four in 10 of the several thousand Chinese facilities AsiaInspection audited last year failed their safety checks, Breteau said. Separately, China’s food safety chief, Bi Jingquan, reported that his agency found 500,000 instances of illegal food safety violations in the first three quarters of 2016.

“Food safety is highly dependent on a culture of food safety, which China doesn’t have,” said Thomas Gremillion, the director of food policy at the Consumer Federation of America. “I don’t see the little bit they’ve done as revolutionizing this permissiveness toward food adulteration.”

But USDA officials say they’re confident that the four facilities approved for export to the United States are safe, even if there have been problems elsewhere. The USDA has visited and inspected those facilities multiple times over the past 10 years — a more rigorous approach than the usual foreign inspection system, in which the USDA lets the food safety arm of the exporting country approve individual operators.

USDA audit reports show that, when problems were found, managers in the four approved plants corrected them to inspectors’ satisfaction.

Those problems included an incident in 2013, when USDA auditors noted that a residue was building up on an industrial tumbler used to process raw chicken at one approved poultry plant.

In 2015, at a separate facility owned by the same firm, auditors observed workers spilling fecal matter onto meat intended for consumption. That plant has not yet been approved to export to the United States, but it is seeking approval under the recently proposed rule.

“There is a lot of pressure on [USDA] to find a way to let China in,” said Tony Corbo, a senior lobbyist with Food and Water Watch who has tracked the Chinese chicken saga for the past decade. But, he added, “we don’t need to import other people’s problems.”

In a statement, USDA spokeswoman Nina Anand said the department has determined that China’s food-safety standards for poultry processing are equivalent to those used in the United States. The agency will also continue to audit Chinese facilities annually, Anand said, and will subject Chinese chicken imports to greater scrutiny upon entry into the U.S. — including laboratory testing, if warranted.

For the time being, such entry inspections will be infrequent. Even under the proposed rule, which would expand Chinese exports, USDA expects China to ship only 324 million pounds of poultry per year over the next five years — roughly 2.6 percent of total U.S. production.

The National Chicken Council, which represents U.S. growers, said in a statement to The Post that it did not expect foreign imports to affect business because U.S. growers maintain a significant competitive advantage. Ninety-nine percent of the chicken that Americans eat is raised and processed here, said Tom Super, a spokesman.

But that could change as China enters the market, critics say. Which is why opponents of the imports are staying vigilant as USDA considers its rule change.

Last week, DeLauro, the Connecticut congresswoman, added a rider to the draft USDA appropriations bill that banned imported Chinese chicken from being served in schools. (It was unanimously approved.) Over the course of the next month, the Democrat also plans to reintroduce legislation that would bar Chinese meat from federal nutrition programs, particularly those for low-income children and seniors.

As for consumers, those with concerns can seek out chicken that's labeled “Hatched, Raised and Processed in the United States,” Super said. It's an option Ronholm, the former head of the USDA food safety office, might consider for himself.

Asked whether he'd serve his family frozen Chinese chicken nuggets, Ronholm demurred.

“At this point, I’m not sure,” he said. “I need more time to see how China is implementing its food safety reforms.”

Link

After 6 months in office, just when is the "You'll be tired of winning. We'll win, win, win," going to start?

When trump loyalists receive their first medical bill showing "coverage denied".

I don't eat chicken, it's a nasty bird

exminister

Well-known member

Then they should pay without insurance. Health insurance is profitable, and loves getting government subsidies.When trump loyalists receive their first medical bill showing "coverage denied".

Good and Bad health are not accidents.

Yes, the germs of wet water fowl like duck are so much healthier.I don't eat chicken, it's a nasty bird

Last edited:

This just in: pelosi may not survive to the end of nightmare intact..

https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=TybQEXN6vLU

Sent from my iPhone using Tapatalk

https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=TybQEXN6vLU

Sent from my iPhone using Tapatalk

Anna, Town, Hex, you idiots.

https://www.snopes.com/miguel-martinez-transgender-bathroom-controversy/

Sent from my iPhone using Tapatalk

https://www.snopes.com/miguel-martinez-transgender-bathroom-controversy/

Sent from my iPhone using Tapatalk

A transgender person raped a girl in a private home. It's a horrible story. Are you trying to tie that to the public bathroom issue?Anna, Town, Hex, you idiots.

https://www.snopes.com/miguel-martinez-transgender-bathroom-controversy/

A transgender person raped a girl in a private home. It's a horrible story. Are you trying to tie that to the public bathroom issue?

Yes, I am you fool.

Sent from my iPhone using Tapatalk

You used a pronoun where an indefinite article would have wrapped it wonderfully.Yes, I am you fool.

Beyond that, it wasn't a public accommodation and no one I've read has ever suggested that you won't find evil intent among any group of people. So...we should outlaw bathrooms? Only let people we're sure aren't rapists or robbers use them?

Would you trust this man with your daughter alone in a room!

Wouldn’t trust you

Sent from my iPhone using Tapatalk

Wouldn’t trust you.

Notice that "intojoy" responded with a "Tillerson" - evading the question because after the "Access Hollywood" tape, no responsible parent would want their daughter alone in a room with Donald Trump, Harvey Weinstein, Bill Cosby, Bill O'Reilly .....

Old news is the norm from jgarbage the Cartoonist.Notice that "intojoy" responded with a "Tillerson" - evading the question because after the "Access Hollywood" tape, no responsible parent would want their daughter alone in a room with Donald Trump, Harvey Weinstein, Bill Cosby, Bill O'Reilly .....