You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

good morning breakfast clubbers

- Thread starter chrysostom

- Start date

annabenedetti

like marbles on glass

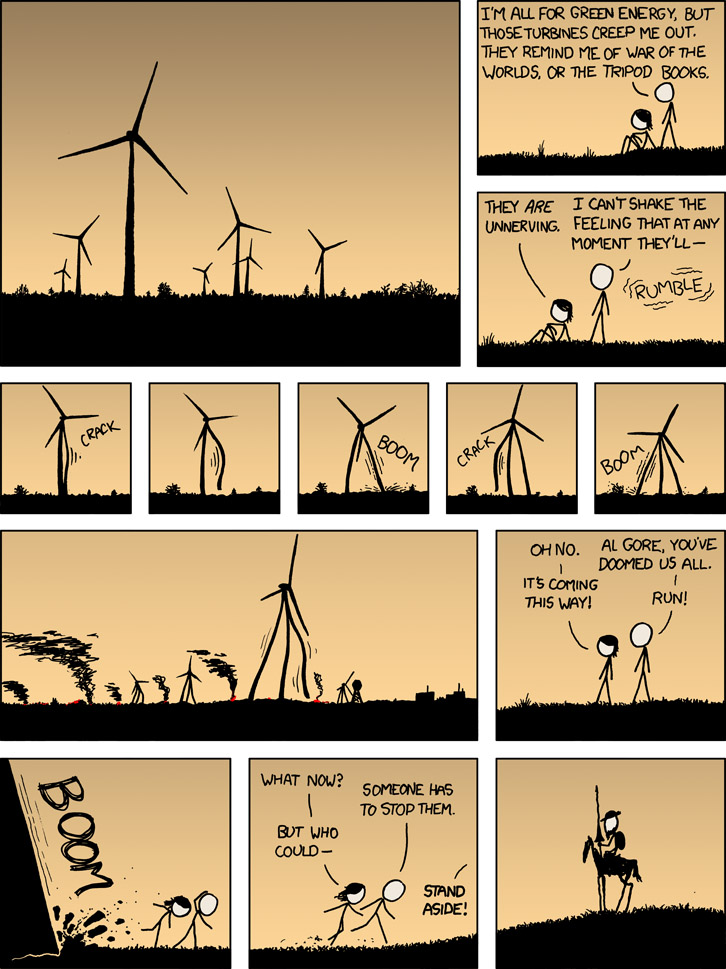

I came across this and of course thought of you, chrys.

For the record, I tried to re-read Don Quixote - must be a couple years ago now - and I could only get through about a third of it. I don't know how I ever managed it the first time, but it was so long ago - I had more patience then. Or maybe I skipped a few pages. Also, I don't think Dulcinea represents the Church, but every reader will come away with something different and unique to themselves, since the book doesn't just speak to us - we speak to the book. It's a conversation.

Also, I don't think Dulcinea represents the Church, but every reader will come away with something different and unique to themselves, since the book doesn't just speak to us - we speak to the book. It's a conversation.

Anyway, here it is.

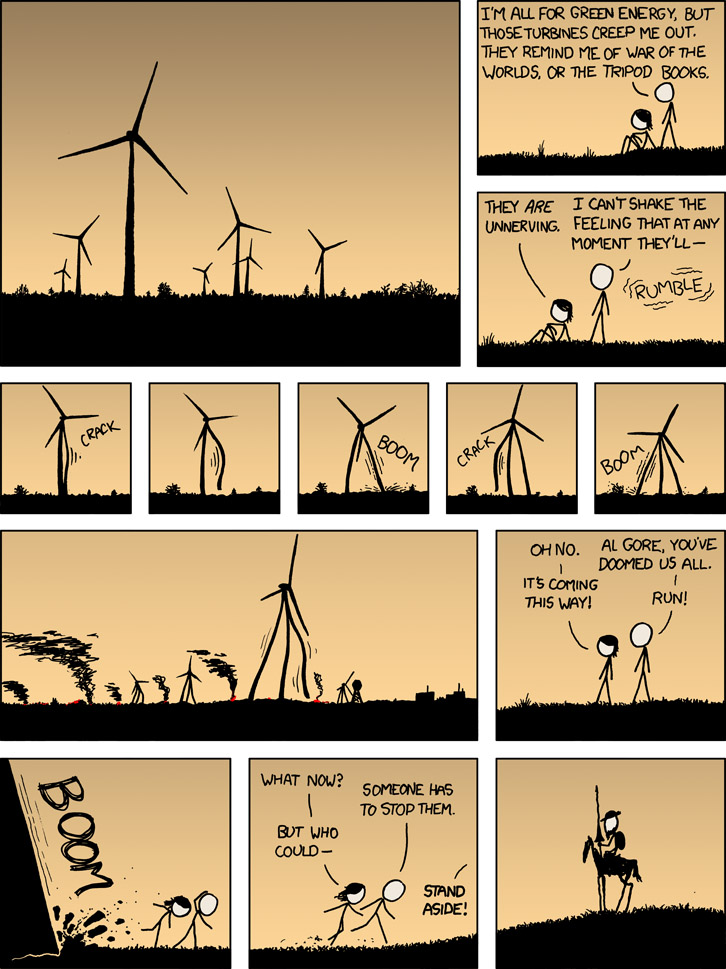

And here's a little something for the breakfast club regulars who made it so special:

For zoo:

For Rusha:

For Arthur:

For kmo:

And for TH:

For the record, I tried to re-read Don Quixote - must be a couple years ago now - and I could only get through about a third of it. I don't know how I ever managed it the first time, but it was so long ago - I had more patience then. Or maybe I skipped a few pages.

Anyway, here it is.

And here's a little something for the breakfast club regulars who made it so special:

For zoo:

For Rusha:

For Arthur:

For kmo:

And for TH:

I don't think Dulcinea represents the Church,

Just found this today

If you don't see him as a crusader and you don't believe it was written by an Arab, you will never see the whore as I see her.

Oh for Pete's sake, there was no Arab writer. Only someone with little familiarity with the period and literature and form or perhaps someone from the FE crowd would believe otherwise. Take a literature course, for Pete's sake...Just found this today

If you don't see him as a crusader and you don't believe it was written by an Arab, you will never see the whore as I see her.

Or, as it was briefly addressed in the NY Times article on the upcoming 400th anniversary of the thing:

We know this is all a jest, as is the very name of the historian: "Cide" is an honorific, "Hamete" is a version of the Arab name Hamid, and "Benengeli" means eggplant.

But this eggplantish historian is no more a jest than anything else in the novel, whether it is Don Quixote tilting at windmills or Sancho Panza governing an island not surrounded by water. Benengeli is, apparently, just as earnest as Don Quixote, just as peculiar and just as important to understanding what this novel is about.

At the time when Cervantes was writing this novel, nothing about this jest was possible. Neither an Arabic-speaking Moor nor a Hebrew-speaking Jew would have been readily found in the Toledo marketplace. And no Moor would have translated Arabic in the cloister of a church.

The Jews had been expelled from Spain in 1492; only converts remained. Books in Arabic had been burned with all the ferocity that the priest applies to Don Quixote's library of chivalric narratives. And while the Muslims hadn't yet been expelled from Spain (that would happen in the years just after the first part of "Don Quixote" was published), they too had to convert.

So Spain was full of New Christians: converts from Islam (called moriscos) and Judaism (called conversos), some continuing to secretly practice their religion (like the Jewish marranos). One reason that pork became such a popular Spanish dish was that eating it was a way to publicly prove one was not following the dietary rules of Islam or Judaism. Eggplant, however, was associated with Muslim and Jewish tastes back when Toledo was home to a flourishing Jewish community.

So Cervantes is up to a bit of mischief with these allusions.

Regarding Cervantes...NY Times, 2005 (link)

Take a literature course,

Instead of reading the book and believing what is written?