You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Election Cheating 2022

- Thread starter Jefferson

- Start date

RINOs in Arizona did it:

RINOs in Arizona - America First Precinct Project

Below is a list of the Republicans In Name Only in Arizona and what they have done to earn that […]

afpp.red

Who Is Rep.-Elect George Santos? His Résumé May Be Largely Fiction.

George Santos, whose election to Congress on Long Island last month helped Republicans clinch a narrow majority in the House of Representatives, built his candidacy on the notion that he was the “full embodiment of the American dream” and was running to safeguard it for others.

His campaign biography amplified his storybook journey: He is the son of Brazilian immigrants, and the first openly gay Republican to win a House seat as a non-incumbent. By his account, he catapulted himself from a New York City public college to become a “seasoned Wall Street financier and investor” with a family-owned real estate portfolio of 13 properties and an animal rescue charity that saved more than 2,500 dogs and cats.

But a New York Times review of public documents and court filings from the United States and Brazil, as well as various attempts to verify claims that Mr. Santos, 34, made on the campaign trail, calls into question key parts of the résumé that he sold to voters.

Citigroup and Goldman Sachs, the marquee Wall Street firms on Mr. Santos’s campaign biography, told The Times they had no record of his ever working there. Officials at Baruch College, which Mr. Santos has said he graduated from in 2010, could find no record of anyone matching his name and date of birth graduating that year.

His financial disclosure forms suggest a life of some wealth. He lent his campaign more than $700,000 during the midterm election, has donated thousands of dollars to other candidates in the last two years and reported a $750,000 salary and over $1 million in dividends from his company, the Devolder Organization.

Yet the firm, which has no public website or LinkedIn page, is something of a mystery. On a campaign website, Mr. Santos once described Devolder as his “family’s firm” that managed $80 million in assets. On his congressional financial disclosure, he described it as a capital introduction consulting company, a type of boutique firm that serves as a liaison between investment funds and deep-pocketed investors. But Mr. Santos’s disclosures did not reveal any clients, an omission three election law experts said could be problematic if such clients exist.

There was also little evidence that his animal rescue group, Friends of Pets United, was, as Mr. Santos claimed, a tax-exempt organization: The Internal Revenue Service could locate no record of a registered charity with that name.

And while Mr. Santos has described a family fortune in real estate, he has not disclosed, nor could The Times could find, records of his properties.

Mr. Santos’s eight-point victory, in a district in northern Long Island and northeast Queens that previously favored Democrats, was considered a mild upset. He had lost decisively in the same district in 2020 to Tom Suozzi, then the Democratic incumbent, and had seemed to be too wedded to former President Donald J. Trump and his stances to flip his fortunes.

His appearance earlier this month at a gala in Manhattan attended by white nationalists and right-wing conspiracy theorists underscored his ties to Mr. Trump’s right-wing base.

At the same time, new revelations uncovered by The Times — including the omission of key information on Mr. Santos’s personal financial disclosures, and criminal charges for check fraud in Brazil — have the potential to create ethical and possibly legal challenges once he takes office.

Mr. Santos did not respond to repeated requests from The Times that he furnish either documents or a résumé with dates that would help to substantiate the claims he made on the campaign trail. He also declined to be interviewed, and neither his lawyer nor Big Dog Strategies, a Republican-oriented political consulting group that handles crisis management, responded to a detailed list of questions.

George Santos hasn't just told one lie, or even just a few lies. He appears to be a total and complete liar about practically everything.

But hey, look on the bright side: He claims to be a homosexual! That's good news to you, isn't it?

Between George Santos and Joe Biden, which one of them has more lies on their resume?

Over a decades-long career, Biden has a lot of lies under his belt, but even though Santos is the new kid on the block, he still beats Biden in the lies category.Between George Santos and Joe Biden, which one of them has more lies on their resume?

Also, Biden has been president for a couple of years now. I haven't heard many lies from him as president. But Santos lies literally almost every time he opens his mouth.

Here is a list of 59 lies Joe Biden has told since taking office.Biden has been president for a couple of years now. I haven't heard many lies from him as president.

Last edited:

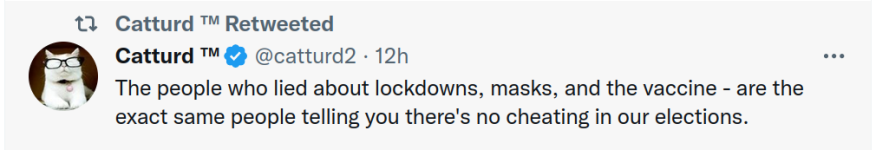

When you refer to "the people who lied about lockdowns, masks, and the vaccine," are you referring to Trump?

Trump told 30,000 untruths during presidency, say analysts

Former president made almost 21 untrue statements a day while in office, analysis suggests

Right Divider

Body part

It's hard to compare numbers that large.Between George Santos and Joe Biden, which one of them has more lies on their resume?

Most democrat sheeple rubes cannot name a fingerful of lies Santos or Trump have told, but as dutiful sycophants of the democrat party, they falsely accuse any and all innocent people their party bosses tell them to slander.George Santos hasn't just told one lie, or even just a few lies. He appears to be a total and complete liar about practically everything.

But hey, look on the bright side: He claims to be a homosexual! That's good news to you, isn't it?

Let's list some of the lies the left claims Trump told: "Trump's statement" followed by "Leftist rebuke."

Trump told 30,000 untruths during presidency, say analysts

Former president made almost 21 untrue statements a day while in office, analysis suggestswww.independent.co.uk

"Good morning..." Leftist retort: "It was not a good morning."

"No president in US history has been treated worse by the opposing party than me" Leftist rebuke: "Trump has been treated better by democrats than any other crook in American history."

"Americans elected me to build a wall to stop the flood of illegal immigration." Leftist exposure of that heinous lie: "There is no illegal immigration crisis, there are no illegal immigrants in the US, and the American people do not want Trump abusing poor refugees who come to the US for refuge and asylum."

And democrats have tens of thousands of other lying stupid responses to the truth spoken by President Trump.

Mike Lindell is going to expose Ron DeSatanist's voter fraud:

Most democrat sheeple rubes cannot name a fingerful of lies Santos or Trump have told

GOP Rep. Nancy Mace lambasted freshman Rep. George Santos on television for lying about his background and experience on the campaign trail.

Mace was asked on CBS News' "Face the Nation" how she could work with Santos after he's admitted to fabricating much of his résumé, and if he should be removed from office.

"It's very difficult to work with anyone who cannot be trusted," Mace said. "It's very clear his entire résumé and life was manufactured..."

Whilst campaigning, Santos lied extensively about his job experience, education, and more.

I am new to this conversation but you can count me as one who believes the 2020 election was stolen for sure

Hi Trump Gurl!I am new to this conversation but you can count me as one who believes the 2020 election was stolen for sure